It was part of a research project tracking variations in sea urchin populations in the Galapagos and how they are affected by the makeup of the sea floor, the prevalence of algae and the presence predators.

Sea urchins are an important link in the aquatic ecosystem, restraining overgrowth of algae that can smother other wildlife and providing tasty prey for such predators as sea stars, Triggerfish, Mexican Hogfish and Spinster Wrasses.

When algae grows sparse, as it does in El Nino years, sea urchin populations tumble along with much of the rest of the marine community. But too many sea urchins can have the same impact, mowing down all the algae, which is an important food source for Green Turtles, Marine Iguanas and many fish.

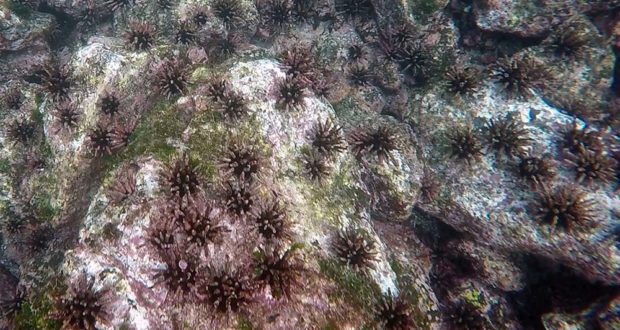

Working with a researcher at the Galapagos Science Center, three of my colleagues and I studied two species: Pencil Sea Urchins (Eucidaris thouarsii) and Green Sea Urchins (Lytechinus semituberculatus). Pencil Sea Urchins are the most common in the Galalpagos, numerous in both shallow and deeper waters. The purplish echinoderms are covered with handful of large, rounded spikes. Green Sea Urchins graze in shallower water. They are more voracious consumers than the Pencil Sea Urchins but are also more vulnerable to the changes in temperature and nutrients that accompany El Nino. They were few and far between during our studies.

Other sea urchin species inhabit the Galapagos waters, including two I came across during my research work. Crown Sea Urchins (Centrostephanus coranatus) have long, black needlelike spikes, and I saw several under rock ledges and in the crevasses of rocks. White Sea Urchins (Tripneustes depressus) have very short, pale spikes and will graze on algae even on exposed rocks.

Sarah Mai, Scott Clark and Rebecca Keim gathering sea urchin data at Punta Carola (Photo/Marc Hanke)

We began our work by laying out underwater transects 30 meters long in the cove at Punta Carola. The water depth varied from about one to four meters. At the 0-, 15- and 30-meter marks on the tape measure, we placed meter-square quadrats on either side that were divided into 16 squares each. The approach is designed to yield a random sampling of the cove that can be extrapolated to the larger area.

For each pair of quadrats we recorded the nature of the sea floor – sandy, smooth rock or rough rock – and the fraction of the quadrat area that was covered in algae. Then, we counted the number of sea urchins and dove to the bottom to measure the body of each with a caliper. That was the most difficult job. The currents were strong, and our wet suits made us buoyant. We had to hold on to a rock with one hand to stay down while we measured sea urchins with the other. We could measure only one or two per dive, and there were as many as 18 at each stop along the transect. All the data went on a plastic “slate” for later analysis. We completed about five transects in the morning each day and punched the data into the computer each afternoon.

Because ecological research is measured in years, not weeks, our work did not produce results but only data that will help support conclusions that may not be reached for quite some time. But there were still a few observations worth noting.

First, within the area we collected data there was nothing but Pencil Sea Urchins, though we saw Green Sea Urchins later when snorkeling at Tijeretas. Second, there appeared to be more sea urchins in the rough lava boulders, where there were crevasses and pockets to hide from predators than in either the smooth or sandy areas. Finally, in some shallower areas the sea urchins were so crowded it was difficult to count them, while in deeper waters they appeared to be much more spread out.